By Alexandros Dimiropoulos

By Alexandros Dimiropoulos

Some cookies are absolutely necessary, as they ensure that certain parts of the website work properly and guarantee its security. These cookies are essential, and will always remain active.

By Alexandros Dimiropoulos

By Alexandros Dimiropoulos

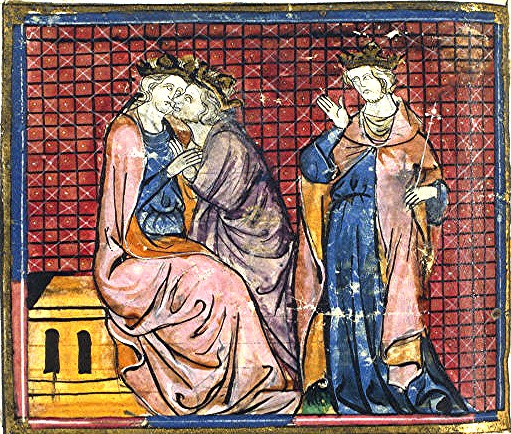

At first glance, The Mouth Kiss (De mondzoen) by Pieter Van der Ouderaa may easily be mistaken for a farewell scene involving a condemned man. Yet what is depicted is not a farewell, but something far more unusual and legally potent: a ritual kiss of forgiveness, which once carried official legal force and could grant amnesty to a murderer.

The scene takes place in Antwerp, Belgium, inside a church. A man who has committed murder appears almost naked, wearing only a white shirt and holding straw—symbols of humility and submission. Facing him stands a young woman dressed in black, a relative of the victim. Behind her, her mother and two siblings look on with a mixture of pain, anger, and stoic restraint.

According to custom, the murderer was required to publicly ask forgiveness from the victim’s family. If the family’s representative kissed him on the mouth, the court clerk would proclaim the official act of reconciliation, and the murderer would no longer be subject to criminal prosecution. The kiss, therefore, was not an emotional gesture but a legal contract.

This ritual was not uniquely Flemish. The earliest known reference to a kiss as a legal act appears within the broader tradition of the kiss of peace (osculum pacis), a ritual with religious and social roots, and is recorded in the legislation of Emperor Henry II in 1019.

The kiss functioned as an oath of peace, a means of resolving conflict, a way to prevent a potential vendetta, and a guarantee that the family renounced any claim to revenge. It was a mechanism through which society could restore balance without bloodshed.

Although the painting shows a woman giving the kiss, historical sources agree that in the overwhelming majority of cases the kiss was given by a man—typically the father, brother, uncle, or legal representative of the family. Medieval law often did not recognize women as heads of household. The mouth kiss carried no erotic meaning; it belonged to a ritual framework traditionally performed between men. Moreover, the act had to express the will of the entire family.

Van der Ouderaa, however, deliberately chose to depict a woman. This choice heightened the emotional impact of the scene, symbolized purity, reconciliation, and moral superiority, and created a more theatrical and dramatic image. Rather than pursuing a cold reconstruction of a historical event, Van der Ouderaa frequently selected subjects charged with strong moral, legal, and psychological significance, emphasizing dramatic tension, emotional restraint, and the symbolic power of the scene.

When the painting was created, in the late 19th century, Belgium was at the center of an intense debate about the future of criminal law. On one side stood the progressive camp, led by Minister of Justice Jules Le Jeune and criminologist Adolphe Prins. They advocated individualized sentencing, the study of the social causes of crime, humane prison conditions, the protection of minors, and suspended sentences.

Opposing them was the conservative Catholic camp, whose leading figure was Théophile Smekens—the man who commissioned the painting. This camp believed that crime was прежде all a sin, that punishment was a moral duty, that the judge should retain paternal authority, and that education and religion redeemed the criminal more effectively than scientific theory. Many among them even supported the death penalty. Smekens wanted the courtroom to be decorated with images that conveyed moral lessons rather than scientific coldness.

A characteristic example of this worldview is La punition du parjure (1888) by Pieter Van der Ouderaa, in which a perjurer kneels repentantly before the Crucified Christ, underscoring the belief that crime is first of all a sin and that justice must be grounded in moral responsibility.

Van der Ouderaa was a master of restrained drama: through dark palettes, realistic details, and controlled emotion, his works—often with legal subject matter—aimed

The Mouth Kiss belongs to the same framework and formed part of the grand decorative program of the Antwerp Cour d’Assises, where the most serious crimes were tried. The painting functioned as a moral and aesthetic foundation of justice, as Smekens wished jurors and spectators to confront a world in which peace, forgiveness, and moral responsibility prevailed over revenge.

The Mouth Kiss is not merely a romanticized medieval scene. It is simultaneously a legal document, a moral reflection, a political statement, and a visual lesson in justice. It reminds us that justice was once a profoundly social and ritual act, in which a single kiss could end a conflict that the court itself might not have been able to resolve. Ultimately, it challenges us to consider what is more difficult: to punish, or to forgive.

Your Comment